Table of Contents

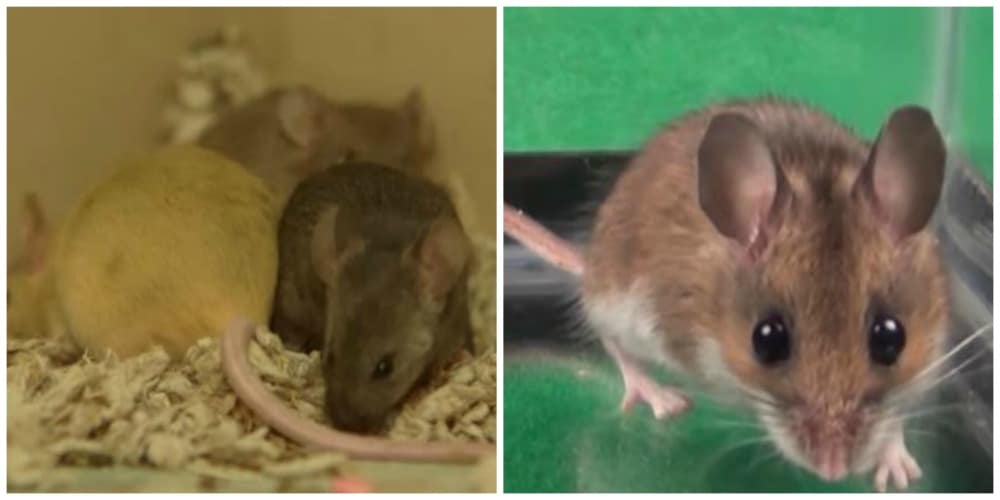

It’s the final showdown – Vole vs Mouse. Which one will succeed in making their home inside of your home? If you’re lucky, you’ll get your way and the answer will be “neither.” But before you can properly defend against small pests invading your house, you need to know how to tell one type from another.

Rats and squirrels aren’t too hard to tell apart, and neither are rats and mice – but voles are so close in size and behavior to many mice that some of them are routinely mistaken for their longer tailed cousins.

Common Mouse Species

The three types of mice you’re most likely to see in your home include:

Deer Mice

Peromyscus maniculatus, commonly known as the deer mouse or white-footed mouse, is common across the entirety of North America. They are less likely to invade urban homes compared to rural ones, preferring the countryside as native habitat. Deer mice are the most abundant small rodent on the continent, and are fully omnivorous – they’ll eat whatever they can find and store leftovers against harsh winter conditions.

The nest of the deer mouse is typically found in any warm, dry spot, such as a hollow in a tree or an abandoned birds nest. They are adept climbers, and will often find their way into a high corner on a shelf, creating a nest from shredded paper and other available debris. They also can make nests under the hoods of old, parked cars using insulation material to build a cozy, cushioned home.

Female mice are fertile at the age of 8 weeks, and in mild climates can breed year-round. They are capable of producing a litter of around half a dozen each time at intervals of approximately one month. Interestingly, a fertilized female can delay implantation if the weather is bad or food supplies are scarce, lengthening her pregnancy allowing her to deliver in more optimal circumstances.

Western Harvest Mice

Reithrodontomys megalotis, also known as the Western harvest mouse, is a very small mouse common throughout the Western U.S. A true opportunist, harvest mice take advantage of abandoned hideaways and trampled down pathways made by larger mice to hide in and travel through.

Like white-footed mice, harvest mice produce feces that can carry hantavirus. A major concern when they enter your home is the feces dust that can get into the air, that you in turn inhale. When they enter a home through the HVAC system, dried feces can be sent out into the air easily. Another common hiding place for harvest mice is in storerooms or pantries out of the way from the hustle and bustle of the rest of the house.

Female harvest mice are exceedingly prolific. With an average lifespan of just one year, a single female can bear 40 to 60 offspring during her short life. The female harvest mouse may mate with multiple males resulting in littermates with different fathers.

The interesting thing about harvest mice is that they can go into what’s called “torpor,” which looks like a light state of hibernation or stasis. This typically only happens when it is very cold and the mouse has been well fed.

House Mice

Mus musculus is the common house mouse. These mice are 3-4 inches long with a 2-3 inch tail, brown fur, and rounded ears. They emit a high pitched “squeak” to communicate with each other and can jump a foot and a half in the air vertically. These are the house mice of fairy tales and poems.

A house mouse typically seeks to build a small nest in an enclosed space, such as behind a wall (think of all those Saturday morning cartoons showing a hole in the wall near the floor). A mouse “family” generally consists of one male mouse with two females, who share the nest, birth near the same time, and nurse each other’s young. Females reach maturity at 6 weeks and can produce up to 10 litters of 3 to 14 young each per 12-month cycle. In optimal conditions, one female could rear more than 100 baby mice in just one year.

The interesting thing about house mice is their tail – they can rear up on two legs and use it as in steadying third leg posture for a threatening “tripod” stance. Additionally, they can direct body heat to the tail where it can leave the body, quickly lowering the overall body temperature if the mouse is too warm.

Common Vole Species

Voles look extremely similar to house mice, with two glaring exceptions:

- Voles have much shorter tails than mice, often only an inch or two in length.

- Voles almost never go into houses if they can help it, they are outdoor animals.

Vole infestations can still be expensive and control needed, as they do millions of dollars of damage to landscaping around residences annually.

The most common types of voles include:

Meadow Voles

Microtus pennsylvanicus is the name for the most common voles; they live in thick vegetation where they will create networked nests, beat down pathways from location to location, and designate a specific area as a common latrine for the colony. They have to eat their body weight every day, are active day and night, and cannot hibernate.

Female meadow voles can have a litter every month, usually numbering around six although only half of them will typically make it to adulthood. The new voles are sexually mature inside of three weeks, making the meadow vole a startlingly prolific breeder despite the high rate of infant mortality.

Meadow voles put vines, plants, and small trees at risk, due to their love of nibbling at the root crown as well as their propensity for “girdling” trees (eating all of the bark in a strip around the trunk of the tree, interrupting the tree’s nutritive supply line).

Prairie Voles

Microtus ochrogaster, known as the prairie vole, is a dark-furred little vole with small ears and a yellow belly, who prefers the drier grasslands to the marshy meadow. These moles also live in colonies. They are unusual for forming pair bonds, and engaging in paired behavior like sleeping curled up together, grooming each other, or bringing each other gifts of food. Voles pair off at mating time, raise a litter, and then become more communal again. They are active year-round, but more diurnal in winter and more nocturnal in summer.

Female prairie voles have 2 to 4 litters of 2 to 7 young per year. The babies are born with ears folded closed and closed eyes; it takes about 8 days for them to unfold their ears and open their eyes. They are weaned at two weeks, and at around 4 weeks can begin breeding another generation.

Prairie moles also do extensive damage, especially in agricultural settings where they can destroy plants and chew holes in irrigation systems. They almost never enter homes but can be chased into one by a predator and become trapped.

The Differences Between Mice and Voles

When it comes to positively identifying a mouse or a vole, four factors can help you make an ID. The ear shape and size, the tail length, and the droppings can clarify in most cases, as can whether the damage is happening inside your home or in your garden.

- Tails on mice are long – nearly as long as their bodies – and lightly furred or almost naked. (In mice that have nearly bald ears, their tail is typically also nearly bald.) Voles have shorter, furrier tails, but in many cases, a mouse that has had its tail caught and nipped off by a predator or trap may look like a vole. Likewise, voles may be mistaken for house mice who have lost a bit of tail.

- Ears are a more dependable way to differentiate many mice from voles – a lot of mice have larger, rounded, pink ears, while voles have short pointed ears covered in fur. Mice, as noted, can lose heat through their tail as well as large hairless ears.

- Droppings can also tell the tale. Mice have hard black or dark brown droppings, about the size and shape of a rice grain. Voles have similarly sized scat, but it is usually softer, green in color, and turns gray as it dries up.

- Damages caused by mice are usually visible inside the home, and evidence of mouse squatters can be found in the form of nesting material, damage to the walls, or other signs of an infestation.

If you see a small, furry intruder indoors that is too small to be a rat, odds are it’s a mouse, not a vole. Mice do major damage to home interiors and garages. Voles, on the other hand, prefer the out of doors, and don’t really want to trespass – but they can wreck expensive landscaping.

To get rid of both mice and voles, natural solutions and repellents can be engaged, allowing you to oust the intruders without causing danger or discomfort to the little creatures just trying to eat, drink, and make more of their kind.